Fixing broken brains: a new understanding of depression

Untreatable depression is on the rise, hinting at fundamental flaws in our understanding of the illness. But new treatments offer hope for everyone

(Image: Michael Glenwood)

ONE OF Vanessa Price’s first chronic cases involved a woman we’ll call Paula. Paula came to the London Psychiatry Centre, where Price is a registered nurse, after two years of unrelenting depression. First she stopped seeing her friends. Then she stopped getting out of bed. Finally, she began cutting herself. Sessions with a psychiatrist didn’t help, nor did medication. In fact, they made it worse. Paula had joined the ranks of people diagnosed with treatment-resistant depression.

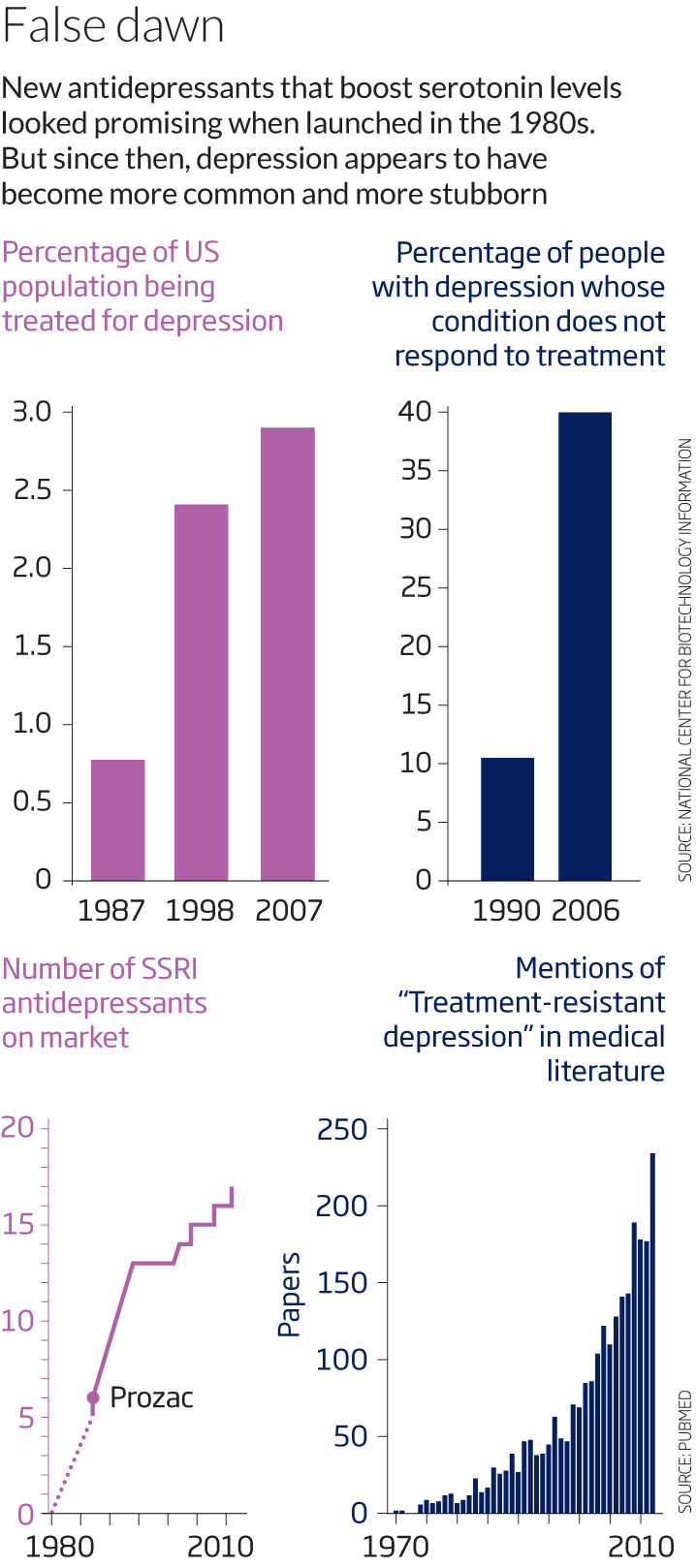

The steady rise in this diagnosis over the past two decades reflects a little-known trend. The effectiveness of some antidepressant drugs has been overstated, so much so that some pharmaceutical companies have stopped researching them altogether.

The stubborn nature of these cases of depression has, however, spurred research into new and sometimes unorthodox treatments. Surprising and impressive results suggest that we have fundamentally misunderstood the disorder.

In fact, the new research has opened the door to thinking about depression not as a single condition but as a continuum of illnesses, all with different underlying neurological mechanisms, which may hold clues to lasting relief. This promise has sparked a renaissance in drug development not seen since the 1950s.

Depression is an illness whose brutality is matched only by its perverseness. Estimates vary, but it is likely that close to one in six of us can expect to struggle with it at some point in our lives. The symptoms are cruel – including insomnia, hopelessness, loss of interest in life, chronic exhaustion and even an increased risk of ailments such as heart disease. Depression also leads people to cut themselves off from others, a tendency exacerbated further by the continuing stigma surrounding the condition, thought to deter over half of depressed people from seeking treatment. Untreated, depression can lead to suicide; the World Health Organization estimates there is one suicide every 40 seconds. These factors all contribute to the WHO’s assessment of depression as the leading cause of disability in the world.

What causes people to become depressed? The dominant theory is that depression results from a chemical imbalance in the brain, with the neurotransmitter serotonin as the prime suspect. Many trials have linked depression to low levels of serotonin, something that was thought to disrupt the brain’s ability to pass messages across synapses, the tiny gaps between neurons.

Mysterious decline

The theory was that a boost in serotonin should return neural signalling and mood to normal levels. The first drug based on the serotonin hypothesis – fluoxetine, better known as Prozac – was launched in the late 1980s, and nearly all subsequent antidepressants have operated on the same general principle: keep levels of serotonin high by preventing the brain from reabsorbing and recycling it.

Though such drugs remain the go-to tools for lifting depression, however, they seem to be getting less effective (see False dawn). Clinical trials in the 1980s and 1990s indicated that these drugs would help 80 to 90 per cent of depressed people go into remission. But studies in the 2000s showed that standard antidepressants work only in 60 to 70 per cent of people, a decline that was underscored in 2006 when the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Bethesda, Maryland published the results of a massive, nationwide clinical trial. Unlike many pharmaceutical trials – which often screen out certain participants – this was the first to measure the effectiveness of antidepressants in a population representative of the real world. The results were disquieting: few of the 2876 participants fully recovered without switching to or in many cases adding other medications.

What can explain this apparent decline in the potency of antidepressants? Perhaps the drugs themselves were never quite as effective as claimed. To approve a given antidepressant, the US Food and Drug Administration only requires two large-scale studies to verify that the drug is superior to a placebo. However, pharmaceutical companies are under no obligation to supply the FDA with every study they have conducted; only the positive ones.

When David Mischoulon, director of psychiatry research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, sifted through previously unpublished data from pharmaceutical trials, he says he found many more negative results than positive ones: a high percentage of studies showed that the drugs were only slightly better than the placebo. “Now we think it’s more in the neighbourhood of 50 per cent of people who may respond to a given antidepressant,” Mischoulon says. So the rise of treatment-resistant depression might be a reflection of the time it has taken doctors to see that reality reflected in their clinics.

The next question then is why – could the drugs’ failure be down to a problem in our understanding of the underlying mechanism? After all, untreatable depression wasn’t the only inconsistency to cast doubt on the serotonin hypothesis. A 2007 study, for example, showed that serotonin levels in the brains of depressed people not receiving treatment were double those in volunteers who were not depressed.

In the wake of this confusion, several pharmaceutical companies decided to stop their work on mood disorders altogether. GlaxoSmithKline – the company that makes the well-known antidepressants Paxil and Wellbutrin – announced in 2010 that it would halt research into depression.

Without new drugs to help the growing number of people whose depression seemed incurable, clinicians found themselves in a bind. “We got used to telling our patients to hang in there,” says Carlos Zarate, a neurobiologist who directs research on mood disorders at NIMH. While they waited for a drug to start working, doctors relied on intense and frequent therapy to ensure depressed people didn’t lose their jobs or attempt suicide. That strategy wasn’t always effective. “I felt like a failure,” Paula says. After nothing worked, she took an overdose of sleeping pills. It wasn’t that she wanted to die, she says; she simply didn’t care if she lived or not.

Last resort

Desperate to help their charges, some frustrated clinicians began to look for new therapies. Their investigations were all over the map: electrical and magnetic brain stimulation, and a veterinary tranquilliser known as ketamine. But they worked.

After drug treatment and behavioural therapy failed, what saved Paula was a groundbreaking therapy called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). It was the stuff of movies. Paula would put a cap on her head and sit under a big machine for about 20 minutes while a brief electric current passed through a small coil positioned a few inches above her left temple, creating a fleeting high-intensity magnetic pulse.

After 15 sessions, Paula stopped wanting to hurt herself. Getting out of bed began to seem like a good idea. When her friends dragged her to a concert, she was surprised to find herself enjoying it. “That would have been unthinkable before,” she says.

“After 15 sessions of magnetic stimulation, getting out of bed began to seem like a good idea to Paula”

Price was surprised. “I have to be honest, I was dubious,” she says. “But I am absolutely stunned by the results.” Since the start of this year, she has successfully treated 10 other people there using rTMS. Price’s experience is reflected in a growing body of research over the past few years, which finds that rTMS seems particularly effective against treatment-resistant depression. In one study, it benefited 12 out of a group of 28 people for whom nothing else had worked.

At the moment, rTMS treatment is not cheap. In the UK, the procedure is not available on the National Health Service, so the people treated at Price’s clinic have to shell out £6000. Australia’s Medical Services Advisory Committee have decided there is insufficient evidence that rTMS works and so have declined to fund such treatments.

In the US, some clinicians have turned to a more affordable option that shows similar promise: cranial electrical stimulation. It simply involves delivering a tiny current with two electrodes strapped to the head using a sweatband. Unlike rTMS equipment, which is bulky, this device is roughly the size of a deck of cards and is available with a prescription.

Stephen Xenakis, a doctor who is also a retired general and a former adviser to the US Department of Defense, uses the device not only on his patients, but also on himself. He asks his patients to use it 20 minutes at a time, twice a day. “Sometimes this can help in ways that the medications don’t,” he says. “The thing I’ve seen it help most with is insomnia and anxiety,” conditions which both fuel, and are fuelled by, treatment-resistant depression.

But the most promising option in terms of convenience could be the drug ketamine. As early as 2000 a study of eight people with long-standing, untreatable depression suggested that a single dose of ketamine, given intravenously, would almost immediately lift symptoms.

Several studies have replicated the results. In the largest clinical trial to date, involving 72 participants, researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, found that people who’d failed to respond to any other treatments experienced relief from suicidal thoughts when given ketamine intravenously for 40 minutes. Zarate says that a growing body of research suggests the drug could work for 60 per cent of patients. “Some people go into remission within a day,” he says, and can remain free from depression for up to 10 days.

But what mechanisms might explain the success of a seemingly unrelated group of treatments where traditional ones had failed? When researchers began to piece together the results, the link they found was glutamate.

Glutamate is the most dominant stimulatory neurotransmitter in the brain, playing a key role in learning, motivation, memory and plasticity. Some researchers think that levels of glutamate, like serotonin, are too low in the depressed person’s brain.

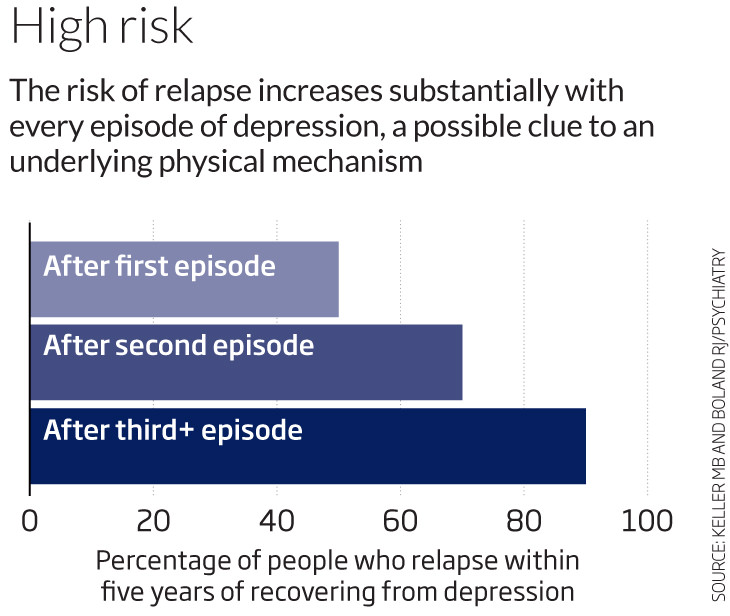

But that’s where the similarity ends. Rather than simply aiding in the transport of messages between neurons, glutamate may be a factor in helping the brain’s neurons repair themselves. This would dovetail with a theory of depression that has gained a significant following in recent years: that depression causes some dendrites – message-relaying “fingers” at the ends of neurons – to shrivel. The synapses become like broken bridges, with messages unable to cross between the affected neurons. Among other evidence to support this theory is the finding that each successive episode of depression seems to leave people more vulnerable to a subsequent episode (see graph).

The ketamine trials were the first clue that glutamate might help. Ketamine sets off a complex chain reaction. First, it blocks the specific receptors that glutamate binds to, releasing a tide of the chemical into synapses. That leads to an increase in a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor which, animal studies show, causes the dendrites to sprout new spines, helping them to receive messages from neighbouring neurons.

When Ronald Duman of Yale University injected rats with ketamine, he saw a burst of glutamate in rodents’ prefrontal cortex – along with a fast increase in the formation of new synapses. Other studies show that rTMS alsoraises glutamate levels to cause similar structural effects.

Instead of enabling a broken brain to pass on messages in spite of damage, then, glutamate may be teaching a depressed brain how to rebuild itself. The feeling, Zarate says, is that in some cases, depression may be better explained as a disorder of neuron structure than being due to a chemical imbalance. But that doesn’t necessarily mean serotonin is out of the picture.

“I don’t think we were wrong,” says Mischoulon. “I think we didn’t have the whole story.” The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of psychiatry in the US, already subdivides depression into categories, including postnatal and bipolar, but it considers their underlying neurophysiological mechanisms to be the same. The new research could change that. “We’re now thinking that there are probably a wide continuum of illnesses lumped together under the heading of depression,” he says, with either glutamate or serotonin as the culprit.

New beginnings

If so, how will individuals know which type of depression they have? One way to find out would be to see which drugs are effective. “If you don’t get a response from ketamine the first day, you probably never will,” says Zarate. Work to develop a diagnostic test is already under way. “We’re trying to identify certain factors in the blood associated with certain subtypes of depression,” says Mischoulon. Brain scans are another possibility: these can already show whether a person will respond better to talk therapy or medication.

All this research is still very much in its infancy, but well before biomarker tests arrive, there should be a raft of new medications that exploit glutamate to combat depression. At least five companies have been working on ketamine derivatives. One example is GLYX-13, which showed promise in preclinical trials earlier this year. AstraZeneca, Roche and Janssen, among others, are also developing both pills and intravenous drugs, the first of which should be with us within a couple of years. Zarate says some pharmaceutical companies are even focusing on glutamate drugs for first line use rather than as a last-resort treatment for depression.

One tantalising possibility remains. If glutamate affects neuroplasticity, could that lead to lasting structural changes in the brain? George Aghajanian at Yale, whose seminal work inspired all the ketamine investigations, says that in people predisposed to recurring depression, ketamine may help neurons permanently maintain new and thicker connections. In recent work on rats, he found that the drug, when combined with other compounds, “leads to long-term structural repairs in the brain”, he says. But whether the same is true in humans will require much further study.

Whatever the future holds, glutamate – and the new possibilities it has raised – has at least enabled us to start thinking about depression in a different way. That is rare in the troubled waters of psychiatry.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please Share and Like Ask Anything You Want..!!